7. J. M. Crook, The British Museum, London and New York, 1972.

8. See B. Mundt, Die deutschen Kunstgewerbemuseen im 19. Jahrhundert, Munich, 1974.

9. Recent efforts to develop a philosophic basis for museum education practices have only deepened their inherent contradictions. The bind arises from two conflicting claims: one proposing that aesthetic experience is universal, definable as such across historical or geographical bounds, and the other appointing the museum as the purveyor and preordained agent of that experience. With this argument museums appoint themselves as both custodians of artifacts and sacerdotes of an educational ideology The American chapelle of populist aestheticians is developing its own manuals, based on pure 1960s ideology and guru parlance, such as M. Csikszentmihalyi's and R. E. Robinson's, The Art of Seeing; An Interpretation of the Aesthetic Encounter, a joint publication of the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Getty Center for Education in the Arts, Malibu, 1990.

10. The precarious nature of Holleins balancing act has been recognized by M. F. Gaskie, "Western Artifice Celebrates Eastem Art" 5, in Architectural Record, 1981, 5, pp. 88-95.

| |

The early European museums, established during the third and fourth decades of the last century, drew heavily on classical architecture, just as they helped enshrine, in their collections of casts and originals, classic art as the measure of all artistic production.7 Yet the subsequent wave of museum buildings that emerged after the middle of the century, both in Europe8 and in the United States, was dominated by less hallowed categories of institutions and objects, many among them dedicated to the arts et métier, natural history, ethnographic documents, or industrial products. The sheer volume of materials amassed for the grand encyclopedic museums of colonial powers was such as to require warehouse-like capacity and highly organized scholarly and administrative expertise. Only the creation of 'modem' collections in the decade before and after the First World War marked a reai reform in museum exhibition practice.

The next phase of museum development with an identity of its own could be called the cultural shopping mall, where the programmatic emphasis shifts from the mass and variety of its holdings to their calculated display for visual consumption. Many traditional museums engaged in major renovation or rebuilding campaigns during the 1960s and 1970s in an effort to shed an appearance faintly reminiscent of dowdy dry goods stores and graduate to one evocative of attractively varied shopping malls that sport ample promenades, snazzy boutiques, cafés, and places of incidental entertainment. To be sure, my thumbnail sketch of the American museum's

historical evolution is of a rather crude order, but I believe it possesses some additional explanatory power, especially when we refine its static categories and recall the particular conditioning each of these major phases imposes on the public's perception of artifacts.

The cultural assumptions goveming the creation of the shrine of the muses, predicated as they are on the rigorous selection of canonic artifacts displayed for their ennobling educational powers, rest on a moralizing devotion to art. Appreciation characterizes the public's attitude, and cultural enrichment is their intended reward. In the warehouse of artifacts, the age of colonialism created its emporia of culture and dignified sheer hoarding by sponsoring systematic study and encyclopedic inventories, grooming in the process an entire profession of museum curators and specialists. The enshrining of auratic masterworks ceded pride of place to the practice of amassing objects of almost every kind, which in turn required the invention of classificatory systems of assembly and display. As a systematic, institutional activity, collecting developed beyond mere accumulation of objects that would occasionally find their way from the far corners of the world into museums.

In the last century of colonialist rule--from the time the Elgin marbles arrived in London (1818) to the installation of the Pergamon Altar in Berlin (1902)--systematic excavations and expeditions, often under the aegis of national museums, yielded new finds in great quantity. Historic study sustained these efforts and directed them into ever-increasing specialization, spawning entirely new departments and spheres of collecting, and even independent museums dedicated to narrowly specialized categories of artifacts.

| |

When we look at nineteenth-century photographs of vast exhibition halls, lined and divided by endless rows of vitrines holding hundreds upon hundreds of objects, we have to admit that their appreciation was obviously not predicated, as it certainly is for us today, on refined strategies of display, nor, as typical museum education parlance would have it, on an ambience "conducive to the enjoyment of the artifacts."9 What Tiffany & Co. and Cartier had done for the stylish merchandizing of a very few select and exceedingly expensive luxury objects, exhibitions like the Metropolitan Museum's The Age of Spirituality (1977) proposed to do for a public with a comparable taste in the hermetic realm of artifacts. These exhibitions reached their apogee invariably in cimelia whose dazzling materials--gold, silver, precious stones, ivory--, workmanship, and provenance constitute the authenticating 'currency' of value itself. No wonder then that Hans Hollein’s installation for the Museum at Teheran (1980) should altogether defy one's ability to distinguish between luxury merchandizing and museum displays.10 These exhibitions effect an ideological foreshortening in the visitor’s experience: they suggest a mirage of ownership by means of a sort of cultural window-shopping.

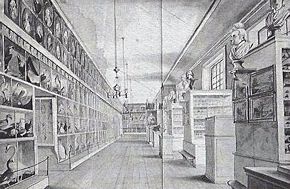

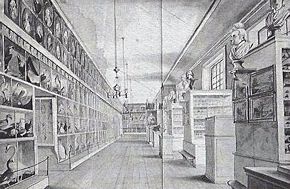

Titian Ramsey Peale The Long Room of the Peale Museum 1822

| |

Keramiksaal in the Königlich-Württembergisches-Landesgewerbemuseum Stuttgart 1896

|

Design for the exhibition The Age of Spiritualaity Metropolitan Museum of Art 1977

| |

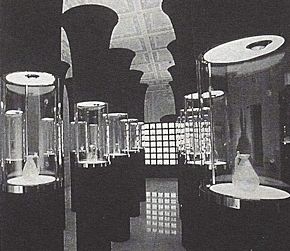

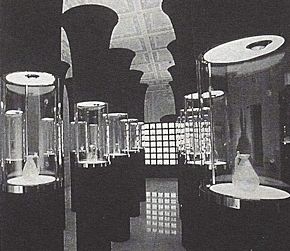

Hans Hollein Design far the Museum of Glass and Ceramics Teheran 1977-78

|

|