Stephen Lauf

The Timepiece of Humanity

The Calendar Incarnate

Annunciation

Duality 1

Duality 2

The Metaphor

The Timepiece of Humanity

The Gauge

Chronosomatically Contemplating the Naval

| |

annunciation

1 : the act of announcing or of being announced : ANNOUNCEMENT 2 also annunciation day usu cap A&D : the 25th of March on which many Christian churches commemorate the announcement of the Incarnation related in Luke 1:26-38

"...it is not uncommon to find the angel and the Virgin each occupying a separate bay in a double arcade...this arrangement [is] almost never absent from Italian representations of the Annunciation..."

"...the Virgin stand[s] in an open portico while the angel advances toward her from the left [and] the column still prevents a complete unification of [the space]."

"...in spatial implications, the dichotomy of the traditional Annunciation arrangement persists, in that the Virgin and the angel are not conceived as occupying a single unified space."

"The traditional conception of the subject called for an exterior setting which was usually rendered as a portico, ...and the arcade with columns produced a division of the space..."

David M. Robb, "The Iconography of the Annunciation in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries," The Art Bulletin, 1936, pp. 486-88.

| |

The Annunciation

The most intriguing aspect of Masolino da Panicale's The Annunciation1 stands right in the middle of the painting. The single column between the angel Gabriel and the virgin Mary is obvious in its central position, yet subtle in its reason for being there. Although the column is right up in front, it nonetheless appears to be in the way, and it is exactly this seeming intrusiveness of the column that makes it difficult to understand why there even is a column.

The only historically established reason for the column's presence is tradition. David M. Robb's extensive study of early Renaissance Annunciation paintings makes it clear that the overwhelming majority of Italian Annunciations employ two distinctive motifs: Gabriel's address to Mary happens within an exterior portico setting, and a column from the portico typically divides the space occupied by the angel from the space occupied by the virgin. Since Robb's study is essentially about the spatial attributes of Annunciation paintings, the bulk of his analysis contrasts the exterior setting of Italian paintings with the interior settings of northern European paintings. Robb only occasionally refers to the "dichotomy of the traditional [Italian] Annunciation arrangement," and pays no attention to the column that is solely responsible for the spatial dichotomy. After studying Masolino's Annunciation, it becomes apparent that the column may be much more important than the spaces it divides.

From an architectural and structural point of view, the placement of Masolino's column is very unconventional. The arches supported by the column suggest two structural alternatives that would be more correct.2 A single column placed under the arch spring-point to the left, or a row of three columns, one under each arch spring-point, are the two logical design solutions. As it is, the column's relationship to the arched canopy produces a highly unorthodox structural cantilever. Given the sophistication of the architectural elements throughout the painting, it is unlikely that Masolino was architecturally incompetent. That he deliberately placed the column in an unexpected structural situation, with the specific intention of calling attention to the column, is a more likely proposition.

There are three other compositional factors within Masolino's painting that emphasize the column. First, the column stands just left of center and creates a slight imbalance. If the column were centered and the picture balanced, no further issue would be made. The off-centeredness of the column, however, catches the eye. Second, the column is the only major element of the painting that is shown complete, unobstructed, and uncropped. The column is in full view, whereas Gabriel's wings and Mary's cloak are not shown in their entirety. Third, as much as Gabriel's and Mary's gazes are aimed at each other, their gazes also appear to be aimed at the column. Furthermore, Gabriel and Mary look as if they are actually paying homage to the column.

|

Now in the sixth month the angel Gabriel was sent from God to a town of Galilee called Nazareth, to a virgin betrothed to a man named Joseph, of the house of David, and the virgin's name was Mary. And when the angel had come to her, he said, "Hail, full of grace, The Lord is with thee. Blessed art thou among women." When she had heard him she was troubled at his word, and kept pondering what manner of greeting this might be.

And the angel said to her, "Do not be afraid, Mary, for thou hast found grace with God. Behold, thou shalt conceive in thy womb and shalt bring forth a son; and thou shalt call his name Jesus. He shall be great, and shall be called the Son of the Most High; and the Lord God will give him the throne of David his father, and he shall be king over the house of Jacob forever; and of his kingdom there shall be no end."

But Mary said to the angel, "How shall this happen, since I do not know man?"

And the angel answered and said to her, "The Holy Spirit shall come upon thee and the power of the Most High shall overshadow thee; and therefore the Holy One to be born shall be called the Son of God. And behold, Elizabeth thy kinswoman also has conceived a son in her old age, and she who was called barren is now in her sixth month; for nothing shall be impossible with God."

But Mary said, "Behold the handmaiden of the Lord; be it done to me according to thy word." And the angel departed from her.

Luke 1: 26-38

incarnation

1 : a clothing or state of being clothed with flesh : taking on of or being manifested in a fleshy body 2 : an incarnated being or idea : as a (1) : the embodiment of a deity or spirit in some form of earthly existence (as a person, an animal, or a plant) (2) usu cap: the union of divinity with humanty with Jesus Christ

| |

As the above examples demonstrate, Masolino skillfully focuses the entire painting towards the column. Tradition alone is no longer a satisfactory explaination for the column's presence. Deeper questions arise. Why is a single column granted so much attention, and what meaning could it possibly represent, in a painting that portrays the Annunciation?

The story of the Annunciation, and hence the subject matter of Annunciation paintings, comes from the Gospel of St. Luke (1:26-38). The angel Gabriel comes to Mary as a representative of God. Gabriel tells Mary that she will conceive in her womb and bring forth a son. The son shall be great and of paramount lineage. Since Mary is a virgin, the words of the angel confuse her. The angel explains that her conception shall be a divine miracle, just as her relative Elizabeth's recent conception was also a divine miracle. Upon this explanation, Mary pronounces that she will serve and assist God, and accepts what the angel has told her. The angel then leaves.

The moment of Mary's compliance with Gabriel's message, when she proclaims herself as "handmaiden of the Lord," is exactly when the Incarnation takes place. It is at this point that "the Word was made flesh..." (John 1:14). The Annunciation and the Incarnation represent both sides of a turning point event. The Annunciation is the very last moment of the separation between God and humanity; a separation that began with the fall of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. The Incarnation, on the other hand, is the very first moment of the reunion of God and humanity. Viewed in this light, Masolino's Annunciation, and all Annunciation paintings for that matter, depict the last moment of separation between God and humanity; the moment immediately before the human conception of Jesus Christ.

|

dichotomy

1 a : division into two parts classes, or groups esp. into two groups mutually exclusive or opposed by contradiction b : division into two : a splitting into two parts or groups : differentiation into two contrasted or sharply opposed groups

duality

1 : the quality or state of being dual or of being made up of two elements or aspects

| |

Turning attention back to the column, it is now appropriate to rephrase the questions concerning the column's possible significance. Why is a single column granted so much attention, and what meaning could it possibly represent, in a painting that portrays the last moment of separation between God and humanity, and the moment immediately before the human conception of Jesus Christ?

As already stated, the column in any Annunciation painting is responsible for creating a spatial dichotomy. Masolino's column, however, goes beyond this traditional notion. The column, together with the small pilaster between the arches, constitutes a clear line extending from the very bottom edge of the painting straight up to the very top. The line virtually divides the painting in half, which means the column does more than just differentiate the space of Gabriel from the space of Mary. With this strong visual separation, Masolino's Annunciation is just shy of being an actual diptych3, that is, a painting composed of two panels hanging side by side with a real separation. Since the dividing line produced by the column only implies a diptych, the separation is not literal, and, rather than create a dichotomy, the column represents a duality that is beginning to bond. This notion of two parts moving towards oneness is the very essence of the Annunciation, and the column itself comes to ultimately symbolize the very last moment of separation between God and humanity.

|

| |

Using a column to symbolize the joining together of two separate entities is an apt choice. In architecture, colonnades are a basic transitional device.4 They clearly mark a boundary, yet to cross through such a boundary is easy. Colonnades facilitate a smooth transition from one realm into another--usually from outside to inside. It is not difficult to permeate a colonnade. Masolino's single column is thus the end result of a "full" colonnade pared down to one final point of separation.

|

| |

There are two other Annunciation paintings that reinforce the conclusions drawn from Masolino's Annunciation. In Fra Fillipo Lippi's Annunciation5 there is a thick, centrally located column creating an exceedingly strong vertical division. Just as in Masolino's painting, the column goes from the bottom edge of the painting straight to the top edge. Although the column does divide the space of the angel from the space of Mary, it is, however, the contrasting quality of light within the two spaces that contributes more to the painting's spatial dichotomy. The space occupied by Gabriel is full of light, where the space occupied by Mary is almost in complete darkness. Lippi's column has nothing to do with the lighting, and, as such, is a strong and independent third party to the painting. It stands for nothing but itself and the visual division it creates. Its sole purpose seems to be one of dividing the painting in two without actually cutting it half. Like Masolino's column, it is representative of a diptych/duality that is beginning to come together.

|

|

|

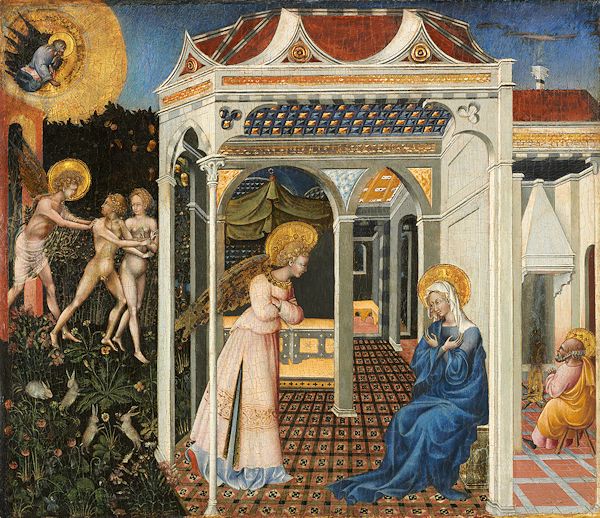

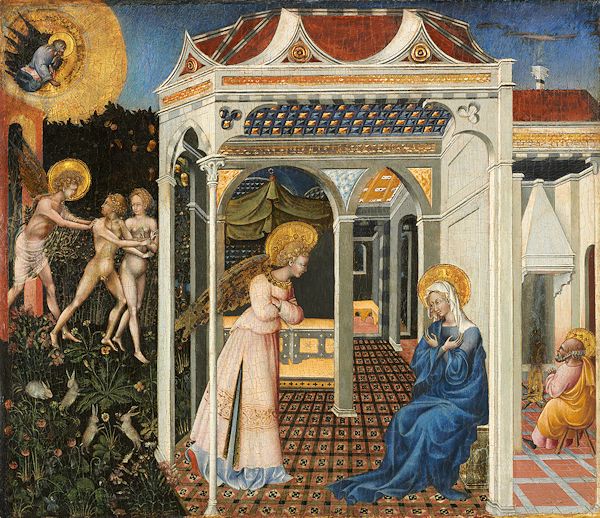

In Giovanni di Paolo's Annunciation and Expulsion from Paradise6, as tradition would have it, a column is present, though it does not create a strong visual line that divides the painting in half. The column between Gabriel and Mary is relatively small and in the background. The important aspect of this painting, however, is the scene going on outside and behind Gabriel. As if in some time warp, Adam and Eve are being expelled from the Garden of Eden at the same time that Gabriel is addressing Mary. This illustrates the aforementioned beginning/end relationship between the "Fall" and the Annunciation. By showing both the beginning and the end of the separation between God and humanity, di Paolo has drawn a full circle, and thereby very uniquely represents the change from separation to unity.

As their paintings illustrate, all three artists show an awareness of the duality between God and humanity that the Annunciation rapidly brings to an end. The artists were also aware that the end of the duality manifested a unity, a singularity. Their main task, therefore, was to portray this duality just as it was about to become a singularity. The duality aspect was easy to portray--Gabriel on one side represents the Divine, and Mary on the other side represents humanity. The Annunciation rendered as a diptych, however, would have too severely pronounced the separation between God and humanity. A "single member," in the form of a column, was, therefore, introduced to the narrative. The column provides the necessary "visual" separation, yet the realistically minimal separation of a single column simultaneously foreshadows the unity and singularity to come. In this light, the column becomes the most potent symbolic figure in the Annunciation's composition since it represents the duality that is ending and the singularity that is about to begin.

|

| |

1. Masolino da Pinacale's The Annunciation (c. 1425/30) is almost five feet tall and four feet wide, painted with wood with oil, and originally served as the alter-piece of the Guardini Chapel in the Florentine church of San Niccolo Oltrano, It now hangs as part of the Andrew W. Mellon Collection in the National Gallery in Washington D.C.

Masolino's Annunciation is a traditional central Italian Early Renaissance Annunciation painting. The Angel Gabrial, advancing from the left, is delivering a meesage from God to Mary, who is sitting and in the midst of reading from the Book of Isaia. This scene takes place in an exterior portico with a background of open doors leading to Mary's bedroom, and the column of the arcade establishes the dichotomy typical of practically all fourteenth and fifteenth century Italian Annunciations.

Masolino di Panicale was a principle Florentine painter of the early Renaissance. He was born in 1383 at Panicale, and thus came from the same district as his younger contemporary Masaccio. Masolino and Masaccio collaborated on projects in Florence and Rome, even though their style's are most times in direct contrast to each other.

Masolino's lyrical style and unfailing artistry is a transition between the Gothic past and the advanced style of the Renaissance.

There is uncertainty surrounding the date of Masolino's death. It is attributed to 1447 but may have occurred at any time after 1435.

More information concerning Masolino di Panicale and this painting is available from the Collection of The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

2. The two drawings above illustrate the compositional results if Masolino were to have portrayed The Annunciation's porch architecture in a more conventional manner. On the left, a single column at the corner supports the entire arched canopy. On the right, the arched canopy is supported by a full colonnade. The full arcade suggests the most reasonable solution, and conversely reinforces the idea that Masolino pared downed the colonnade to emphasize the central column.

3. The drawing to the right illustrates Masolino's Annunciation as a true diptych. It is easy to imagine these two panels as the outside face of an altarpiece that can be opened up. It is also worth noting that the strong central band is very similar, in effect, to the broad column in Fra Filippo Lippi's Annunciation.

| |

|

4. The Temple of Aphaia at Aegina and the Altes Museum in Berlin are just two examples of colonnades used to effect transition and permeability. In the temple plan, to the left, a continuous colonnade surrounds the sanctuary thereby relating the building to the entire landscape and allowing accessibility from all directions. In the museum plan, right, the front and entrance of the building are expressed through a long colonnade followed by a shorter one. In both plans, the use of inner columns further facilitates penetration into the buildings.

5. Filippo Lippi's The Annunciation (probably after 1440) is over three and a half feet tall and over five feet wide (1.029 x 1.626 m), painted with tempera on wood, and was persumably once a lunette that has been cut at the top, the sides, and along the bottom. It now hangs as part of the Samuel H. Kress Collection in the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

Lippi's Annunciation employs a central column that creates a spatial dichotomy, and thus partially follows the tradition of early Renaissance Italian Annunciations. That both Gabriel and Mary occupy interior spaces, however, is a divergence from the Italian tradition. Furthermore, Lippi heightens the spatial dichotmy through a severe lighting contrast between the two spaces. The darkness behind Mary may symbolize the "darkness" befallen to humanity since the sin of Adam and Eve; a darkness soon to be vanquished by the "light" of Jesus Christ.

Fra Filippo Lippi was a well known and influential Tuscan painter of the 15th century. He was born in Florence in 1406. His father died during Filippo's youth, and his mother subsequently gave the boy over to the Carmilite friars of Sta. Marie del Carmine in Florence. Lippi took his first vows at the age of 15, and was first mentioned as a painter in 1432, at the age of 26. Lippo's training as a painter was contemporary with Masaccio's and Masolino's fresco painting in the Brancacci chapel in the Carmine.

Lippi left the Carmilite order about 1431, and lead a sucessful painting career into his sixties. At the age of sixty he married a nun, Lucrezia Buti, who became the mother of the painter Filippino Lippi.

Lippi died at Spoleto on Oct. 9, 1469

More information concerning Fra Fillipo Lippi and this painting is available from the Collection of The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

6. Giovanni di Paolo's The Annunciation and Expulsion from Paradise (c. 1445) is approximately 16 inches high and 18 inches wide, painted on wood, and belonged to a predella (a step or platform on which an altar is placed). Other parts of the predella are: The Nativity in the Vatican Museum; The Crucifixion in Berlin; and The Circumcision in New York. It now hangs as part of the Samuel H. Kress Collection in the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

Giovanni's Annunciation contains one large central scene with two smaller scenes to either side. On the left, the Archangel Michael drives Adam and Eve out of the Garden of Eden, while above them is the Almighty surrounded by a large golden circle. In the center, the Annunciation takes place in an open portico composed of five differently styled arches. Gabriel enters from the left, and Mary sits on the right with here hands crossed before her breast. On the right, in a side room, Saint Joseph sits on a stool facing a fire.

The Annunciation portion of the painting follows the traditional Italian formula of an exterior portico and a dividing column. The column, though, does not actually create a spatial dichotomy. This painting is distinctive, however, in its simultaneous depiction of Adam and Eve's Fall from the Garden of Eden and the Annunciation. Giovanni has here depicted both the beginning and the end of humanity's separation from God. With the oncoming Incarnation, we see Saint Joseph, literally in the wings, waiting to fulfill his role in the New Covenant.

The painting is full of juxtapositions, as well as transitions. From left to right, we see the past, the present, and the future. The Annunciation, the present, is the true point of transition--a transition from separation to unity. The column between Gabriel and Mary, however, does not represent transition as much as the two arches it supports. The arch above Mary is pointed; a distinct Gothic attribute. The arch above Gabriel is round; a distinctly un-Gothic trait. The juxtaposition of these two arches not only represents the transition that occurred at the Annunciation, but also represents the transition from Medieval times into the Renaissance; a transition that Giovanni himself was working in the midst of.

Giovanni di Paolo was a prolific and individualistic Sienese painter throughout his long life. He was baptized Nov. 19, 1403 and died in 1482. Giovanni had a particular gift for painting narratives, and many alterpieces he painted for Sienese churches are now dispersed among European and American collections. He was influenced by contemporary artists in both Siena and Florence.

Giovanni's changing vision of the world is illustrated in his painting styles. The colorful and attractive figures and landscapes of his early and middle period become harsh and ugly in the 1460's and 1470's. His agitated spirituality and expressionistic style were unpopular in this century until about 1920.

More information concerning Giovanni di Paolo and this painting is available from the Collection of The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

|