piranesi |

1956 |

|

A more analytical reading, generating from the more flamboyant aspects of his pictorial work, may help us to understand and resolve the proposed problem.

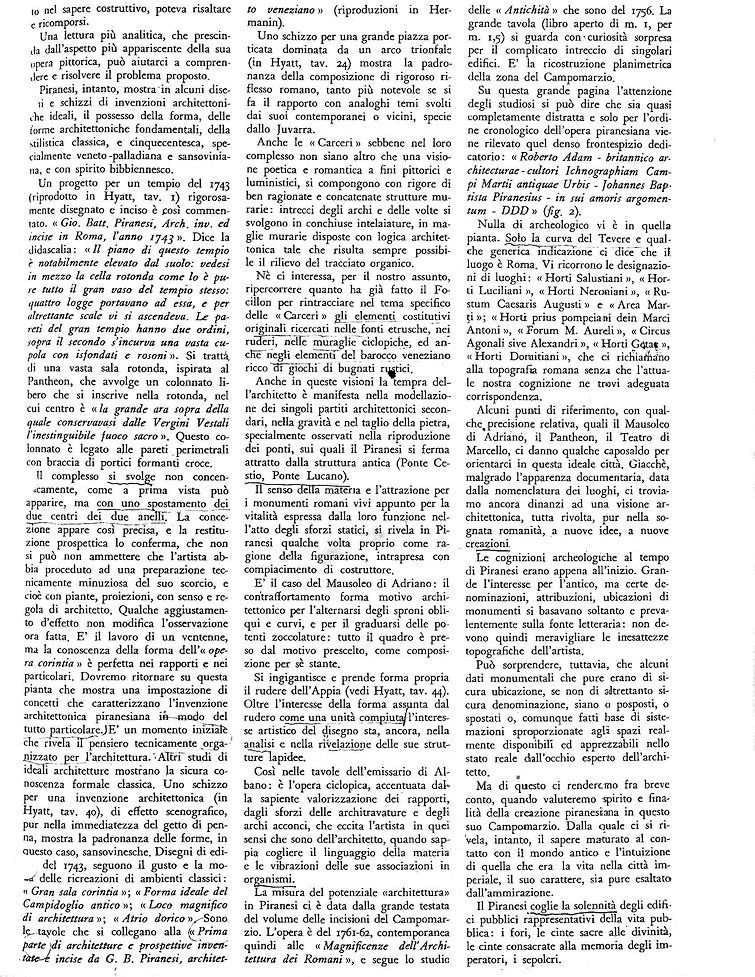

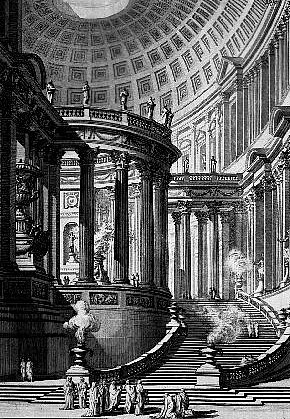

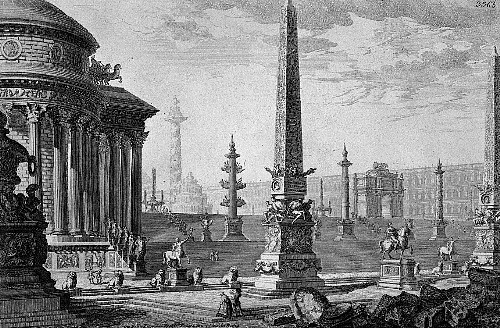

A sketch for a great porticoed square dominated by a triumphal arch shows his command of compositions of strict Roman provenance, more notable if one makes connections to analogous themes developed by his contemporaries or neighbors, especially Juvarra. Even the "Carceri", which in their totality are nothing but a poetic and romantic vision with pictorial and resplendent ends, are composed with a well reasoned rigor and with linked mural structures: the interlacing of arches and vaults unfold in a resolved framework, in mural networks arranged with an architectural logic that makes possible a projection of the structural scheme.

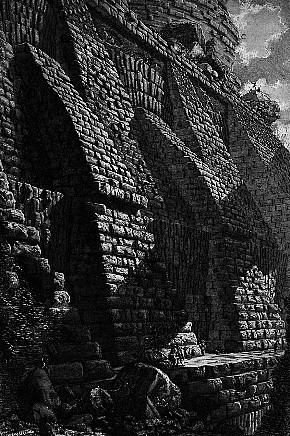

Even in these visions the temper of the architect is manifested in the modeling of the secondary architectural details, in the weight and cut of the stone, particularly observed in the reproduction of bridges, on which Piranesi lingers attracted by their antique structure (the Cestio and Lucano bridges).

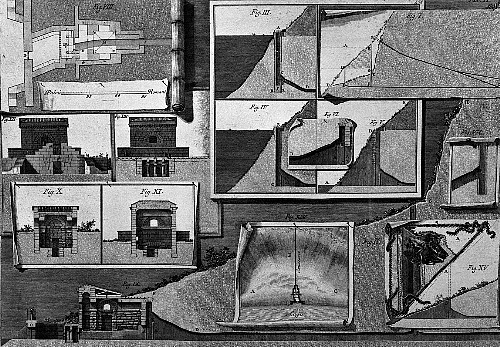

Again in the plates of the sluice gates of Albano: it is a gigantic work, accentuated by a knowing appreciation of its references, by the pressures of the architraves and the arches, which excites the artist in those senses that belong to the architect that knows how to grasp the language of the material and the vibrations of its associations with living things.

|

|

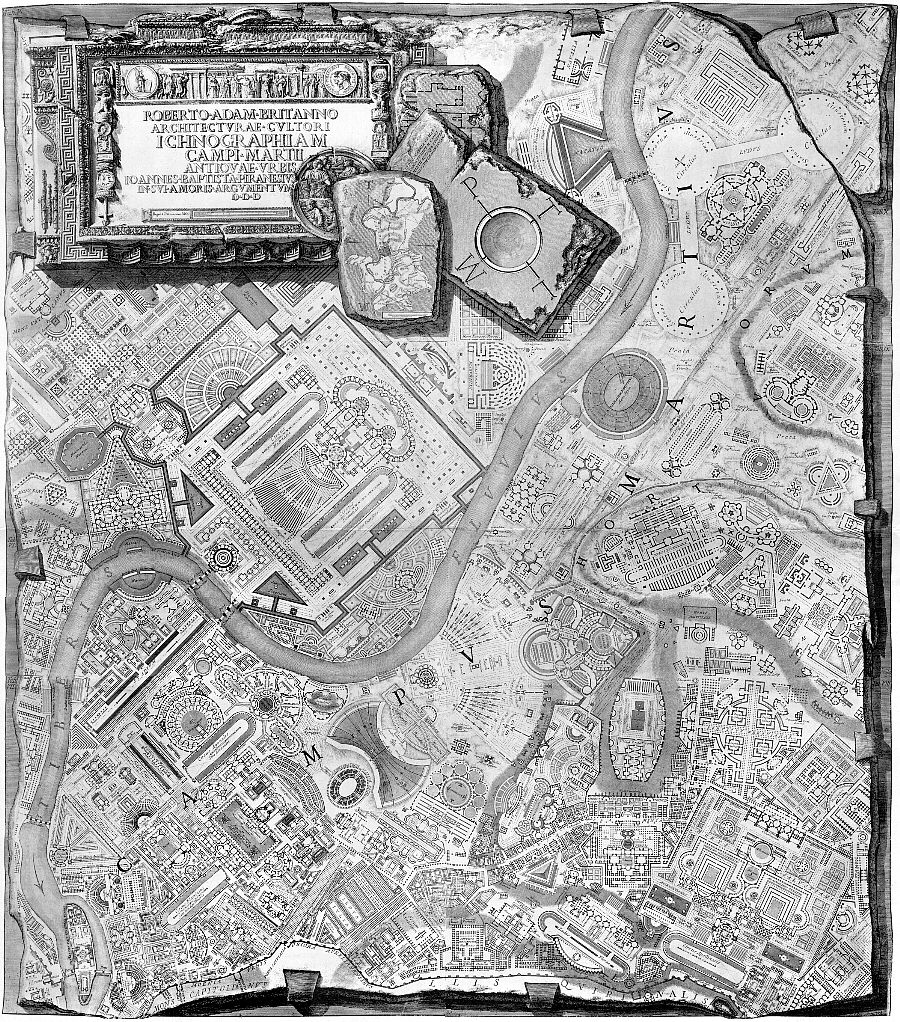

The measure of the potential "architecture" in Piranesi is given to us by the great head-butt that is the volume of engravings of Il Campo Marzio. The work is from the years 1761-62, contemporary, then, to the Magnificenze dell'Architettura dei Romani, and follows the studies of Le Antichit� Romane from 1756. The large plate (open book dimensions of 1 meter by 1.5 meters) is examined with curiosity, and one is surprised by the complicated interlacing of singular buildings. It is a plan view of the reconstruction of the Campomarzio area.

On this great page, one can say, the attention of scholars has always been completely distracted, and only the chronological ordering of the Piranesian opus revealed the dense dedicative frontispiece: Roberto Adam - britannico architecturae - cultori Ichnographiam Campi Martii antiquae Urbis - Johannes Baptista Piranesius - in sui amoris argomentatum.

Fasolo's statement regarding the Ichnographia's lack of "archeology" was echoed when Tafuri said "the archeological mask of Piranesi's Campo Marzio fools no one." Tafuri goes on to say the Ichnograpia "is an experimental design and the city, therefore, remains an unknown."

|

|

|

|

|

|

Quondam © 2020.09.07 |