2013.08.07 12:10

Learning from Learning from Las Vegas (again)

I'll start with something I posted almost one year ago within The Philadelphia School (deterritorialized):

Ideas for the Bicentennial were first published within the October 1969 issue of The Architectural Forum--" The Bicentennial Commemoration 1976"--a rare piece of writing where Denise Scott Brown precedes Robert Venturi as co-author. Seen now in retrospect, many of the ideas proposed were ground-breaking and indeed influential in the long run, and still relevant today with regard to current notions of architecture and advocacy. To offer one flavor of the piece I parsed out the sentences that contain the words 'little' and then the sentences that contain the word 'big':

"It is significant that Expo 67, hailed as a triumph, produced little innovation in architecture or structure."

"Still very much employed and perhaps even more challenged, since now their ingenuity would be taxed to make much out of the little available for building, to make meaningful in built structures the serious aims of the nation, and on top of this to make our show fun, seductive and delightful."

"The Commemoration should serve, starting now, as a major aid to economic development of the black community, otherwise we shall have little to celebrate in 1976."

"Why should Little Upper Begonia strive to show us its plastic factory when it has so much to say on the harnessing of teen-age revolt or on the housing of rural migrants?"

"An Expo based on interaction of people in meeting places spread over several cities could look a little low."

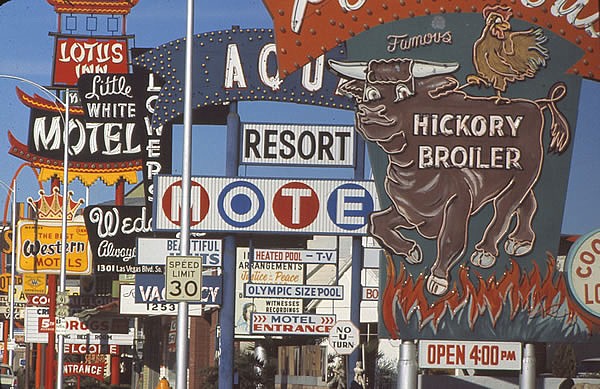

"We recommend, because of the social tasks, the use of modest buildings with big signs."

"We advocate, because of the social tasks, the use of modest buildings with big signs."

There is an authors' note at the end of the piece:

We owe much in the development of our ideas to Mr. Tom Wolfe (who coined the phrase "electrographic architecture"), to Mr. David A. Crane, to members of the Philadelphia Bicentennial International Exposition Planning Group, and to the Philadelphia Citizens' Committee to Preserve and Develop the Crosstown Community, and all their advisors.

This brings to mind a curious footnote within Charles Jencks' The Story of Post-Modernism (2011):

Tom Wolfe lampooned architects' inability to reach the exuberance of Las Vegas sign artists, or 'Electrographic Architecture', in many articles. One key essay, republished in his collection The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, Farrar, Straus & Giroux (New York), 1965, was written in his neo-hysterical style--'Las Vegas (What?) Las Vegas (Can't hear you! Too noisy) Las Vegas!!!' Tim Vreeland has told me that when Venturi and Scott Brown were visiting Albuquerque circa 1968, he put a copy of Wolfe's book on the bedside table, and the couple were so impressed they drove off to see Las Vegas the next day. Their own shift in taste-culture towards commercial vernacular and Route 66, culminated first in an article, 'A Significance for A&P Parking Lots' (1968) and then the whole argument, Learning from Las Vegas, MIT Press (Cambridge, MA/London), 1972. Thus the Las Vegas polemic may date from Wolfe's humorous assault on professional taste, and that he too was to carry on with another attack on Minimalist Modernism, From Bauhaus to Our House, Farrar, Straus & Giroux (New York), 1981. Reyner Banham took the Las Vegas sign artists in another direction, towards the dematerialized city of electronics, light, and environmental control. His The Architecture of the Well-tempered Environment, Architectural Press (London), 1969, inverts the Corbusian definition of architecture--'pure forms seen in sunlight'--to 'coloured light seen in impure forms'.

To clear up some of the chronology suggested above:

1965: On her way to California to teach in the School of Environmental Design at Berkeley for the spring semester, Scott Brown stops off in Las Vegas. That summer she travels in the southwest. In September, Scott Brown moves to Los Angeles and accepts the position of co-chair of the Urban Design Program at UCLA, where she remains through 1967. She recruits Venturi to act as a visiting critic.

1966: Scott Brown invites Venturi to visit Las Vegas with her for a four-day trip. In November the two travel the Las Vegas strip, from casino to casino, being alternately "appalled and fascinated" by what they see. [ Venturi says, "Next I was taken to Las Vegas in 1966 by Denise Scott Brown--prepared a little by Tom Wolfe and a lot by Baroque Rome. Out of that trip came our studio at Yale and then our book Learning from Las Vegas."]

Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture is published by the Museum of Modern Art as the first in an intended series of occasional papers addressing issues of architecture and design (actual distribution is not until March 1967).

- - - - -

I have not yet read 'Las Vegas (What?) Las Vegas (Can't hear you! Too noisy) Las Vegas!!!' but it's clear that Venturi and Scott Brown have. They also accepted Wolfe's challenge for architects to "reach the exuberance of Las Vegas sign artists." The truth may actually be "prepared a lot by Tom Wolfe and a little by Baroque Rome."

And before Wolfe, there was Peter Blake's God's Own Junkyard: The planned deterioration of America's landscape (1964, which I'm reading now). Here, Venturi and Scott Brown take an anti-thetical point of view: they try very hard to establish a positive view of billboards and roadside honky-tonk.

Both Blake and Wolfe were the inspiration and laid the ground work for what became Learning from Las Vegas. Blake already shows up at the critical ending of Complexity and Contradiction where Venturi proclaims "Main Street is almost alright"--the beginning of the antithesis. Then, of course, the Long Island Duck comes out of God's Own Junkyard, and many of the commercial strip/honky-tonk images presented negatively by Blake are virtually identical to the commercial strip/honky-tonk images presented positively by Venturi, Scott Brown and Izenour.

What I've read so far in God's Own Junkyard is about anti-billboard sentiment/legislation from the late 1950s/early 1960s. Inspired by Wolfe, Venturi and Scott Brown have taken a pro-billboard stance. For example, in Blake we read: "...quotes beautylover Burr L. Robbins as saying that "billboards are the art gallery of the public." Mr. Robbins is the President of the General Outdoor Advertising Co., Inc. ...since "billboards are the art gallery of the public," his industry might enhance its public image by donating valuable billboard space in cities and countryside to display huge reproductions of such historic masterpieces as the "Mona Lisa," "Blue Boy," "Song of the Lark," and "Lavinia." In 1975, Venturi and Rauch's City Edge's Planning Study proposed virtually the exact same idea.

I feel confident that a close reading of God's Own Junkyard, 'Las Vegas (What?) Las Vegas (Can't hear you! Too noisy) Las Vegas!!!' and Learning from Las Vegas in tandem will manifest a strange new alchemy.

| |

2013.08.08 10:17

Learning from Learning from Las Vegas (again)

Here are some passages from God's Own Junkyard (pp. 20-21) on 'symbolism' [with interjections from today] which may be key to how the notion of symbolism is rendered throughout Learning from Las Vegas:

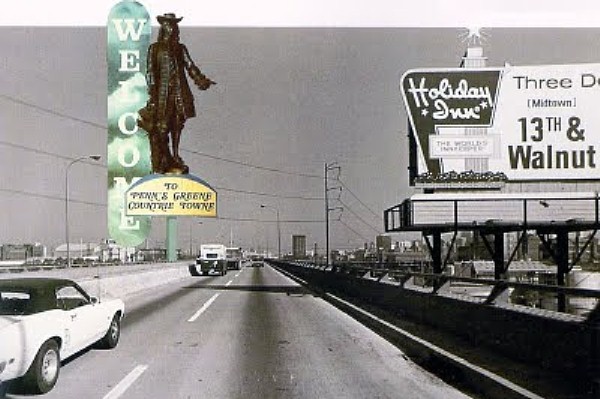

"As for symbolic buildings, what do we see in Suburbia? It is true that there are probably some churches along the nearest highway. But while the churches of our early New England towns and villages were tall enough (and sufficiently close by) to be visible from almost anywhere, the sprawl of today's Suburbia has pushed the churches so far out that that their spires are no longer visible farther than a block away. (The Howard Johnson spire, more often than not, is more visible.) [In antithetical fashion, the thinking of Learning from Las Vegas looks for the 'symbolic' significance of the likes of the Howard Johnson spire.] This condition may, of course, be an accurate reflection of today's relative values, but it is also a further contribution to the formlessness of modern Suburbia. One of the important functions of a tall building in any community is to serve as a point of reference, to permit people to find there way about without troble, much as a lighthouse helps a ship's captain to chart his route. [In Learning from Las Vegas we find large casino signs analyzed as 'lighthouses' aiding the navigation of automobiles along the Strip.]

Suburbia's other "symbolic" buildings are those of the shopping center, which is certainly symbolic of something--though perhaps not of anything we would particularly want to symbolize. [Hence "The Significance of A&P Parking Lots."] (Some new shopping centers have tried to become "community centers" in a broader sense, and perhaps there is some validity in this.) Then there are schools, police stations, fire stations [From LfLV page 130: "The total image of our U&O fire house--an image implying civic character as well as specific use--comes from the conventions of roadside architecture that it follows: from the decorated false facade, from the banality through familiarity of the standard aluminum sash and roll-up doors, and from the flagpole in front--not to mention the conspicuous sign that identifies it through spelling, the most denotative of symbols: FIRE STATION NO. 4."] and, indeed, somewhere, there may even be a town hall. [See Venturi & Rauch's Three Buildings for Canton, Ohio, as featured in Complexity and Contradiction.]

The meaning of all this is twofold: first, we do not seem, at this time, to possess the sort of common faiths that shaped cities like Florence (whose only tall building were the symbols of religion and of government) or, at least, we do not seem to be very strongly committed to any common faiths; and, second, one reason we are not committed is, quite clearly, that nobody living in Suburbia (and very few people living in Urbia) is conscious of the physical symbols of democratic government--the one faith we do claim to hold in common." [Wasn't Learning from Las Vegas, without explicitly saying so, trying to disclose the new "common faiths that shape" our cities?]

Also there is this passage from God's Own Junkyard (p. 23) which unwittingly percurses the whole notion of learning from someplace like Las Vegas:

"There is, as a matter of fact, one American city that does continue to gleam; that city; of course, is Miami Beach--the gleamingest place south of the polar icecap. Alas, its gleam can hardly be said to be "undimmed by human tears." For here, in the glittering collection of our most astonishing architectural acrobatics, the affluent society has finally gone berserk! This is the ultimate junkpile--that mysterious place our television stars must mean when they talk of "Videoland." [Wait! Don't tell me that God's Own Junkyard also inspired Koolhaas's 'Junkspace'?] Here the vulgarians have outdone themselves: if Miami Beach did not exist, the enemies of America would have to invent it. Happily for them, unhappily for us, they can spare themselves the trouble. If only, as someone has said, Miami Beach were as good a lesson as it is an example..."

2013.08.16 12:06

Invisible Architecture

...somewhat reminded of the contrast of (old) Fremont Street (Las Vegas) during the day and at night.

Does the notion of the Decorated Shed somehow relate to 'Invisible Architecture'?

| |

2013.08.18 17:35

17 August

...I'm picking up Wolfe's Kandy-Koloured... book of essays tomorrow, so I'll be adding more to the Learning from Las Vegas discussion soon. Plus, I want to review what you already wrote and the article you linked, especially with regard to what I most recently wrote about God's Own Junkyard. It seems your suspicion of a false naivete is more true than not.

2013.08.26 14:13

Learning from Learning from Las Vegas (again)

Here are two more passages from God's Own Junkyard that relate to later (antidotal) sentiments within Learning from Las Vegas.

"Where men once decorated their rooftops with gilded finials, we decorate ours with tar-papered watertanks, pipes, smole stacks, vents, aerials, and illuminated billboards. Like children, we insist upon labeling most of our buildings, putting the name of the owner or tenant up on top in giant letters: one of the tallest, most prominently situated skyscrapers in the world, for example, is now crowned with the cryptic, mammoth words "PAN AM" (some sort of tribal chant, apparently) because the owners were persuaded by their publicity advisers that this giant badge was worth (exactly) $1 million per year in advertising! And yet we smile, a bit condescendingly, when we see the churches bearing signs that promise "JESUS SAVES" and similar good tidings."

The above may well have inspired this 1965-66 antidotal architectural response:

Likewise...

2007.07.13 Found what may be the most sarcastic (but also the most critical) passage within the "ugly and ordinary" texts of Learning from Las Vegas: "The Boston City Hall and its urban complex are the archetype of enlightened urban renewal. The profusion of symbolic forms, which recall the extravagances of the General Grant period, and the revival of the medieval piazza and its palazzo pubblico are in the end a bore. It is too architectural. A conventional loft would accomodate a bureaucracy better, perhaps with a blinking sign on top saying I AM A MONUMENT."

The penultimate paragraph of God's Own Junkyard:

"At present, these should-be leaders are, instead, performing for Mr. Ripley's "Believe It or Not" circus: architects, painters, and sculptors are outdoing one another in acrobatics, in hot pursuit of novelty; taste makers are busy watching the box office and the circulation figures, instead of making taste; and the public (which includes the public uglifiers) simply follows the lead of our supposed "intellectual elite.""

|