21 August 1778 Friday

. . . . . .

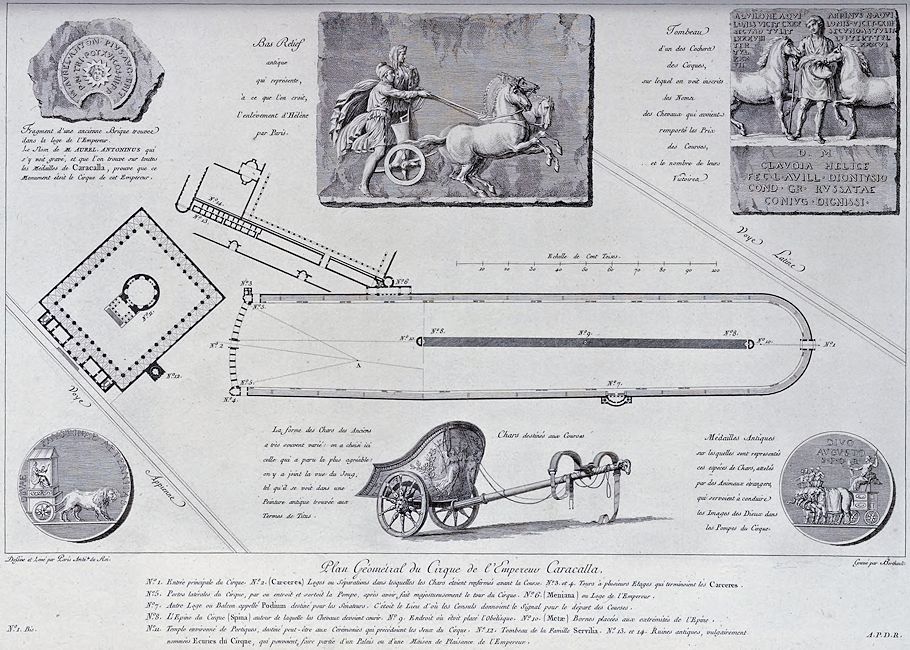

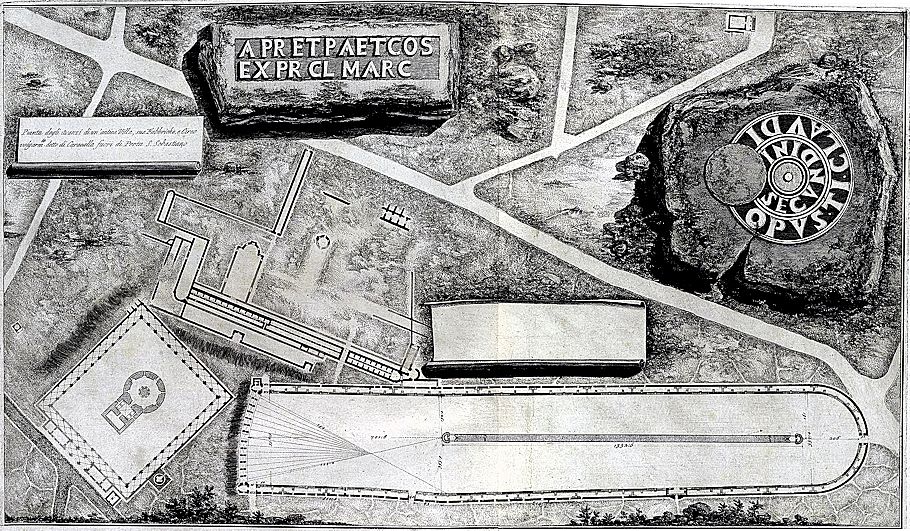

Artifacts of the Bianconi vs Piranesi 'Circus of Caracalla' affair 1772-1789

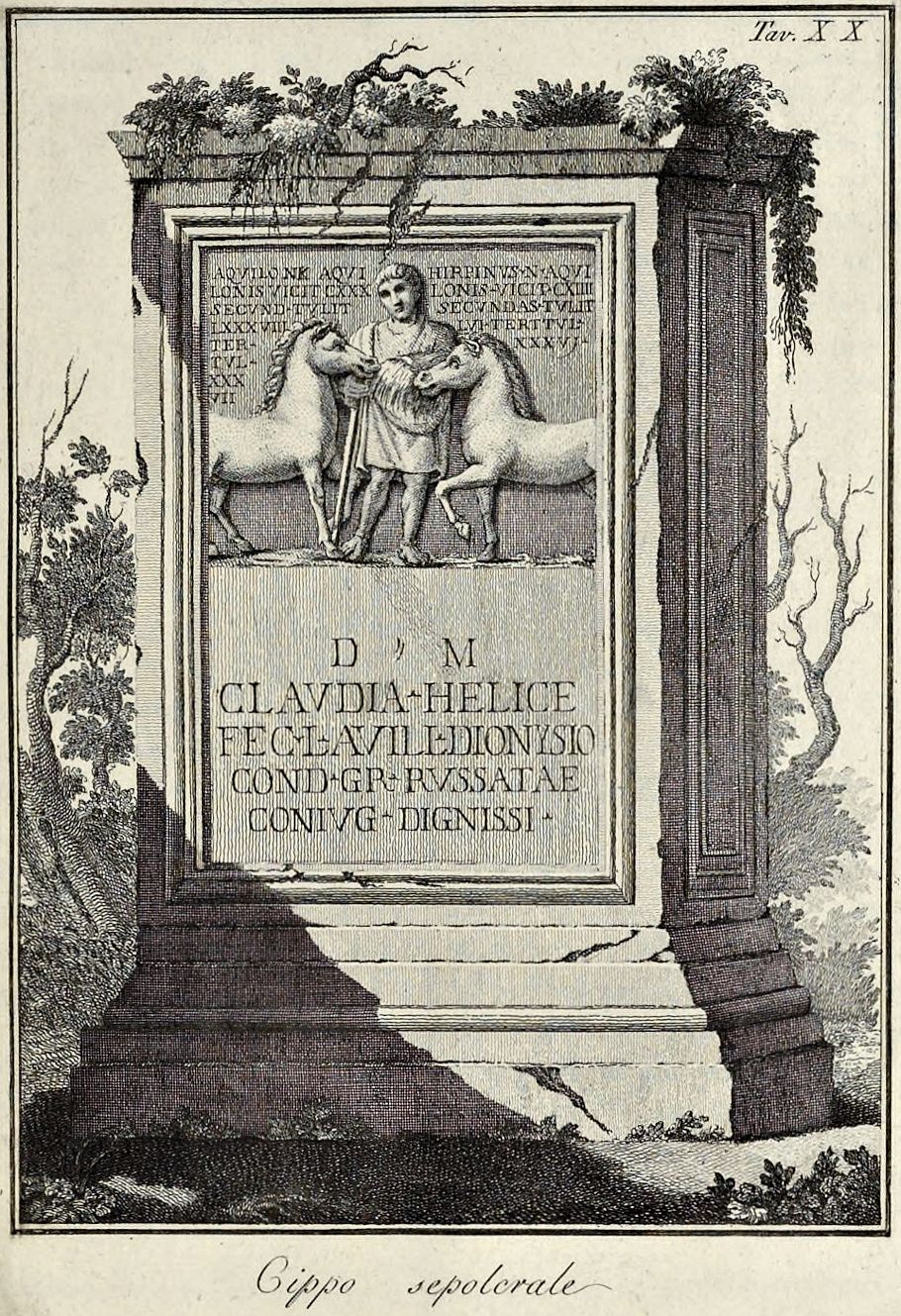

Tavola XX Sepulchral cippus.

48 y.o. Francesco Piranesi 1806

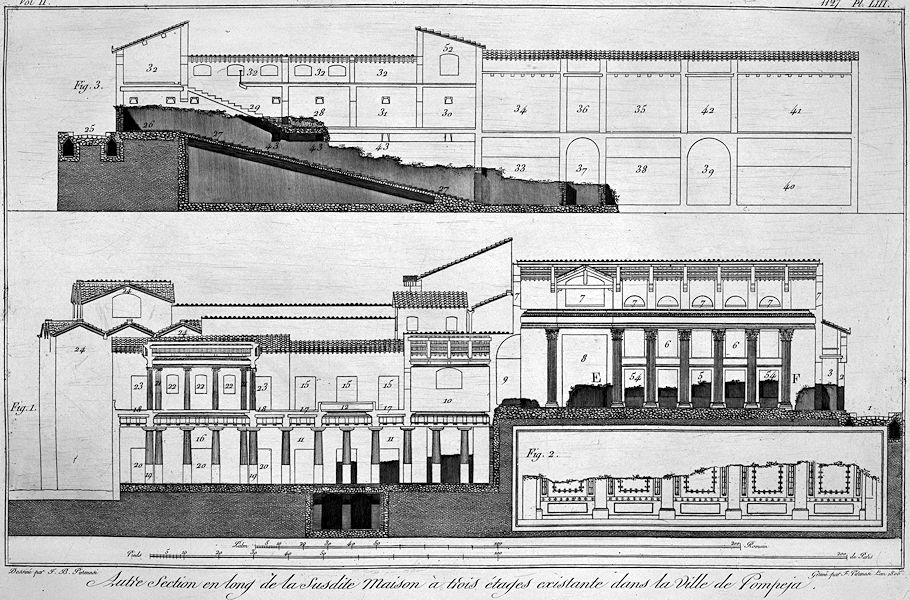

Le Antichità della Magna Grecia Parte II

Other Longitudinal section of the above existing three-storey house in the City of Pompeii.

Drawn by G.B. Piranesi

Engraved by F. Piranesi Year 1806

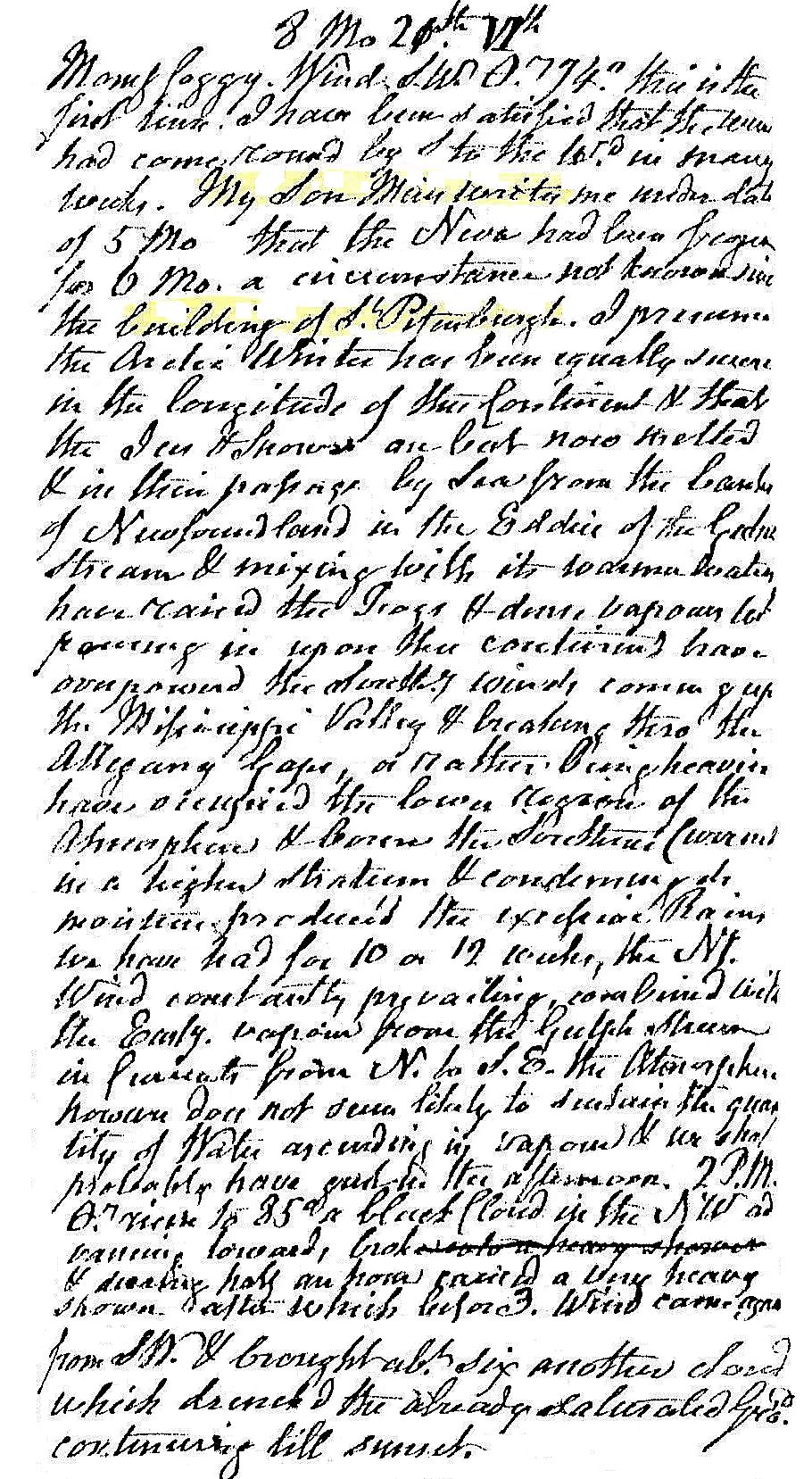

21 August 1812 Friday

Morning foggy, wind SW, temperature 74°. This is the first time I have been satisfied that the wind had come round by S to the westward in many weeks. My son Miers writes me under date of May [blank] that the Neva had been frozen for 6 months; a circumstance not known since the building of St. Petersburg. I presume the arctic winter has been equally severe in the longitude of the continent and that the ice and snows are but now melted and in their passage by sea from the banks of Newfoundland in the eddies of the ..... stream and mixing with the warmer waters have raised the fogs[?] and dense vapors let[?] ....... in upon the continent have overpowered the southerly winds coming up the Mississippi Valley and breaking through the Allegany Gaps, or rather, being heavier, have occupied the lower regions of the atmosphere and borne the southern current in a higher stratum and condensing all[?] moisture produced the excessive rains we have had for 10 or 12 weeks. The northerly wind constantly prevailing, combined with the early vapors from the Gulph Stream in ........ from N to SE. The atmosphere however does not seem likely to sustain the quantity of water ascending in vapor and we shall probably have ........ this afternoon. 2 PM temperature rose to 85°. A black cloud in the SW advancing towards broke into a heavy shower and during[?] half an hour rained a heavy shower after which before 3 came round from SW and brought about 6 another cloud which drenched the already saturated ground continuing till sunset.

21 August 1977

21 August 2017

Virtual Painting 461

21 August 2023 Monday

On 10 October 2022 I wrote, "I wish I had the time today to further translate and analyze Focillon's passages regarding the 1772 Righi affair at the Accademia de S. Luca and Piranesi's counter proposal." I auto-translated the passages, Henri Focillon, Giovanni-Battista Piranesi (Paris: H. Laurens, 1918), pp. 103-6, today:

En 1762, l'architecte Pio Balestra avait institué l'Académie héritière de toute sa fortune, pour augmenter les fonds destinés aux concours. A côté des concours capitolins, institués au début du dix-huitième siècle par Clément X, restaurés par Benoit XIV, il y eut les concours Balestra. En 1772, l'affaire, qui semble avoir été retardée par des procès avec les héritiers naturels, était réglée par un compromis, et l'Académie s'occupait d'élever un tombeau à son bienfaiteur dans l'église Saint-Luc. Dans sa séance du 6 septembre, elle avait choisi l'un des trois modèles présentés par le sculpteur Tommaso Righi, après avoir écarté les projets qui eussent entraîné des dépenses excessives. Elle arrêta les bases d'un contrat entre Raphaël Mengs, alors prince de l'Académie, et l'auteur désigné du monument. Mais l'affaire revint en question le 2 octobre, et il est probable que c'est au cours de cette séance que Piranesi, qui jugeait insuffisant le projet de Righi, se laissa emporter au point de frapper un contradicteur. Le procès-verbal ne mentionne pas le fait expressément: l'on conviendra qu'il était difficile de lui donner une forme académique. Mais il y fait une allusion significative, en parlant "des disputes et des altercations qui firent naître quelque désordre entre certains seigneurs académiciens". Cette séance orageuse fut levée à une heure avancée, sans qu'on eût pu traiter les questions pour lesquelles la "congrégation" était convoquée.

Le même jour Piranesi adressait à Mengs un long factum où il exposait d'une manière plus précise son sentiment sur le projet de Righi, sur les exigences du cadre architectural où devait être élevé le tombeau de Balestra, sur la nécessité de ne rien faire qui ne fût d'accord avec l'art de Pierre de Cortone. "C'est lui l'auteur de l'église. Il a cru que les dispositions établies n'en seraient jamais altérées... II a confié son œuvre aux soins d'une Académie composée des hommes les plus respectables de tous les temps." Il discute la convenance du lieu qu'il faut choisir. Il invoque à chaque instant la dignité du corps dont il fait partie et le respect que l'on doit aux œuvres des grands artistes. Son imagination prévoit une adaptation harmonieuse du sanctuaire à des besoins du même genre. "L'église deviendra une sorte de galerie par la juste symétrie d'autant d'autres monuments qu'il y aura de bienfaiteurs de l'Académie." Il fait appel au passé. "Autrefois, sur les monuments funéraires, on élevait des statues, soit en pied, soit dans l'attitude que réclamaient le sujet du tombeau et les lieux où il devait être élevé." Il rêve, pour celui de Balestra, quelque groupe élégant, bien isolé, en pyramide, d'un caractère allégorique, comme ceux qui décorent l'autel de Saint Ignace, dont il loue la disposition "parce qu'elle est conforme à la manière des anciens". Y aurait-il un inconvénient à dresser une figure héroïque représentant une vertu, par exemple le culte des arts libéraux, sous la forme d'un génie allégorique appuyé contre une urne lacrymatoire, adapté à la circonstance et aux idées du temps? "Un pareil monument, écrit-il en s'adressant à Mengs, devrait être exécuté d'une manière digne de votre principat." Un simple panneau sculpté, un médaillon, ce sont là des projets trop peu généreux de la part d'une assemblée si respectable, et le bienfaiteur de l'Académie aurait le droit d'être mécontent. De tout temps, rien ne fut plus honorable qu'une statue: rien ne saurait mieux marquer la reconnaissance des

artistes envers Balestra. En terminant, Piranesi rappelle à Mengs que chaque membre de l'Assemblee a le droit d'exprimer librement son opinion. Il reclame la convocation du corps tout entier, pour pouvoir deliberer d'une manière franche et complète. Il est sans doute fâcheux de revenir sur une décision déjà prise. Mais, lorsqu'il s'agit de l'administration d'un royaume, quand bien même le souverain aurait déjà réglé quelque affaire, il n'hésite pas à modifier ses résolutions, après avoir pris conseil, si le bien de l'État l'exige. Righi peut protester s'il lui plait: l'Académie est la maîtresse de lui donner ses ordres, puisque c'est elle qui fait la dépense. Elle est composée d'hommes compétents, au fait de tous les arts libéraux. Elle doit juger en dernier ressort, au mienx de ses intérêts et de sa gloire.

La matière est infertile et petite, mais là comme ailleurs Piranesi se donne tout entier. Aucun objet n'est à ses yeux limité. Tout ce qui touche à la dignité des arts intéresse son infatigable ardeur. De l'église Saint-Luc il fait une galerie de morts illustres, un panthéon des bienfaiteurs de l'école italienne. La question qui occupe l'Académie est pour lui affaire d'état; l'assemblée en séance est un parlement. La fièvre de son imagination vivifie et agrandit tout ce que les circonstances lui présentent. Mais son plaidoyer devait demeurer inutile. Il en fut donné lecture au début de la séance du 24 octobre. On vota sur la question de savoir s'il fallait s'en tenir au projet de Righi ou adopter les propositions de Piranesi: ces dernières furent repoussées à l'unanimité. Ordre est donné au trésorier de compter à Righi 125 écus pour commencer à traiter son modèle dans la grandeur d'exécution. Il existe à Saint-Luc un petit monument Balestra, vivant, amusant et coloré, malgré ses proportions modestes. On le croirait à première vue surchargé d'ornements, mais il n'en est rien. L'adresse de la composition meuble les vides et donne l'illusion de l'ampleur et du mouvement. Des amours entourent une targe gondolée sur laquelle se lit l'inscription commémorative. Le motif principal de la décoration est emprunté aux attributs traditionnels du peintre. C'est l'œuvre la plus aimable et la plus médiocre. Elle fait penser à un frontispice de Choffard, arrondi à l'italienne. On eût aimé à voir Piranesi se donner carrière dans un genre pour lequel il était particulièrement doué.

Piranesi tint-il rigueur à ses confrères de l'exclusion donnée à son projet? Son nom est extrêmement rare dans les registres des séances. Il faut

attendre le 11 octobre 1778 et le principat de Preziado, pour le retrouver, en compagnie de son ancien rival Tommaso Righi. Il est plus curieux de constater que les procès-verbaux ne portent aucune trace de sa mort, alors que celui du 3 juillet 1779 enregistre le chagrin général que causa la perte de Raphaèl Mengs et mentionne les dispositions prises pour la célébration des messes accoutumées en l'honneur des académiciens disparus. On s'en étonne d'autant plus que l'on voit scrupuleusement notées des morts qui intéressent beaucoup moins les arts, celle des deux sœurs de Placido Costanzi ou celle de Costanza Liofredi par exemple. Peutêtre les honneurs académiques n'étaient-ils pas absolument indispensables à la gloire de Piranesi. Dans tous les cas, il ne paraît pas avoir été fait pour l'activité mesurée qui règne dans ces assemblées. Une fois de plus, c'est à ses œuvres qu'il faut recourir pour être franchement en contact avec sa nature et son génie. Plus que les événements ordinaires de sa vie, que nous ne pouvions pourtant négliger et qui comportent leur part de signification, elles permettent de le comprendre et de l'interpréter. En reprenant leur histoire au point où nous l'avions laissée, nous retrouvons ce qu'il y a d'essentiel dans le cours de ces années, l'ordre de faits le plus riche et le plus explicite de son existence.

In 1762, the architect Pio Balestra had instituted the Academy, inheriting all his fortune, to increase the funds intended for competitions. Alongside the Capitoline competitions, instituted at the beginning of the eighteenth century by Clement X, restored by Benoit XIV, there were the Balestra competitions. In 1772, the affair, which seems to have been delayed by lawsuits with the natural heirs, was settled by a compromise, and the Academy took care of erecting a tomb for its benefactor in the church of Saint-Luc. In her session on September 6, she had chosen one of the three models presented by the sculptor Tommaso Righi, after ruling out projects that would have involved excessive expenditure. It established the bases of a contract between Raphaël Mengs, then prince of the Academy, and the designated author of the monument. But the matter came up again on October 2, and it is likely that it was during this session that Piranesi, who considered Righi's project insufficient, got carried away to the point of hitting an opponent. The minutes do not mention the fact expressly: it will be agreed that it was difficult to give it an academic form. But he makes a significant allusion to it, speaking of "the disputes and altercations which gave rise to some disorder between certain academic lords". This stormy session was adjourned at a late hour, without it having been possible to deal with the questions for which the "congregation" was convened.

On the same day Piranesi sent Mengs a long factum in which he explained more precisely his feelings on Righi's project, on the requirements of the architectural framework in which the tomb of Balestra was to be erected, on the need to do nothing that did not agree with the art of Pierre de Cortona. "He is the author of the church. He believed that the established dispositions would never be altered... He entrusted his work to the care of an Academy composed of the most respectable men of all times ." He discusses the suitability of the place to be chosen. He constantly invokes the dignity of the body of which he is a part and the respect that we owe to the works of great artists. His imagination foresees a harmonious adaptation of the sanctuary to similar needs. "The church will become a kind of gallery by the right symmetry of as many other monuments as there will be benefactors of the Academy." It appeals to the past. "In the past, on funerary monuments, statues were erected, either standing or in the attitude required by the subject of the tomb and the places where it was to be erected." He dreams, for that of Balestra, of some elegant group, well isolated, in a pyramid, of an allegorical character, like those which decorate the altar of Saint Ignatius, whose arrangement he praises "because it conforms to the manner ancient". Would there be a disadvantage in erecting a heroic figure representing a virtue, for example the cult of the liberal arts, in the form of an allegorical genius leaning against a tear urn, adapted to the circumstance and to the ideas of the time? "Such a monument, he wrote, addressing Mengs, should be executed in a manner worthy of your principality." A simple sculpted panel, a medallion, these are too ungenerous projects on the part of such a respectable assembly, and the benefactor of the Academy would have the right to be dissatisfied. At all times, nothing was more honorable than a statue: nothing could better mark the recognition of

artists to Balestra. In closing, Piranesi reminds Mengs that every member of the Assembly has the right to freely express their opinion. It calls for the convocation of the whole body, in order to be able to deliberate in a frank and complete manner. It is undoubtedly regrettable to go back on a decision already made. But, when it comes to the administration of a kingdom, even if the sovereign has already settled some business, he does not hesitate to modify his resolutions, after having taken advice, if the good of the State requires it. Righi can protest if he pleases: the Academy is the mistress to give him his orders, since it is she who makes the expense. It is composed of competent men, familiar with all the liberal arts. She must judge in the last resort, in the minex of her interests and her glory.

Matter is infertile and small, but there as elsewhere Piranesi gives himself entirely. No object is in his eyes limited. Everything that touches the dignity of the arts interests his indefatigable ardor. From the church of Saint-Luc he made a gallery of illustrious dead, a pantheon of benefactors of the Italian school. The question occupying the Academy is for him an affair of state; the assembly in session is a parliament. The fever of his imagination vivifies and enlarges all that circumstances present to him. But his plea was to remain useless. It was read out at the beginning of the October 24 session. A vote was taken on whether to stick to Righi's plan or adopt Piranesi's proposals: the latter were unanimously rejected. Order is given to the treasurer to pay Righi 125 écus to start treating his model in execution size. There is a small Balestra monument in Saint-Luc, lively, fun and colorful, despite its modest proportions. It looks at first sight overloaded with ornaments, but it is not. The skill of the composition fills in the voids and gives the illusion of breadth and movement. Cupids surround a warped targe on which the commemorative inscription can be read. The main motif of the decoration is borrowed from the traditional attributes of the painter. It is the loveliest and most mediocre work. It is reminiscent of a frontispiece by Choffard, rounded in the Italian style. We would have liked to see Piranesi pursue a career in a genre for which he was particularly gifted.

Did Piranesi hold it against his colleagues for the exclusion given to his project? His name is extremely rare in the registers of the sessions. It's necessary wait until October 11, 1778 and the principate of Preziado, to find him, in the company of his old rival Tommaso Righi. It is more curious to note that the minutes bear no trace of his death, whereas that of July 3, 1779 records the general grief caused by the loss of Raphaèl Mengs and mentions the arrangements made for the celebration of the customary masses in honor of deceased academicians. We are all the more surprised that we see scrupulously noted deaths that are of much less interest to the arts, that of the two sisters of Placido Costanzi or that of Costanza Liofredi for example. Perhaps academic honors were not absolutely essential to Piranesi's glory. In any case, it does not seem to have been made for the measured activity which reigns in these assemblies. Once again, it is to his works that one must have recourse to be frankly in contact with his nature and his genius. More than the ordinary events of his life, which we could not however neglect and which carry their part of significance, they make it possible to understand it and to interpret it. By resuming their history at the point where we left it, we find what is essential in the course of these years, the richest and most explicit order of facts of its existence.

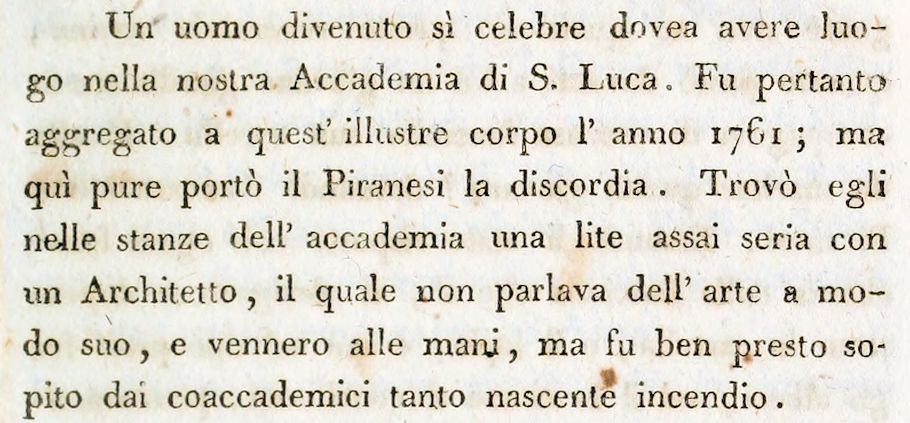

Bianconi mentions the 2 October 1772 incident in Elogio storico del cavaliere Giovanni Battista Piranesi, celebre antiquario ed incisore di Roma:

A man who became so famous had to take place in our Academy of S. Luca. It was therefore aggregated to this illustrious body in the year 1761; but here too Piranesi brought discord. In the rooms of the academy he found a very serious quarrel with an architect, who did not speak of art in his own way, and they came to blows, but the nascent fire was soon put to sleep by the co-academics.

On 3 July 2023 I wrote, "The 2 October 1772 event may well be what made it easy for Bianconi to disparage Piranesi's Circus of Caracalla work; Bianconi feeling sure those "that mattered most" would be on his side." At the time, I did not know that it was Pierre-Adrien Pâris who was working individually, though simultaneously, with both Piranesi and Bianconi with regard to the Circus of Caracalla. If Pâris presented his asymmetrical circus plan drawing to Bianconi some time after 2 October 1772, and Bianconi, at that same time, learned that Piranesi was also involved with the plan drawing, then, most likely, Bianconi's rejection of the Pâris/Piranesi work was highly and emotionally charged: "Mr. Piranesi divulged the plan drawn by that same mercenary [Pierre-Adrien Pâris], who worked so sincerely for our Author, and in the same manner, that is to say, full of dreams, and of enormous blunders, fruit either of malice, or of crass ignorance, or of lightheadedness."

Pâris circa 1773

Piranesi 1778.06.21

|